A part of living in Anglophone countries is finding yourself in several rooms with monolingual people. I find that monolinguals in England are oddly fascinated by the ability to speak multiple languages—perhaps reminding them of their Latin or French lessons in school that went nowhere—and when you mention that you speak more than two, they’re endlessly fascinated by it. The conversation never veers towards reading in more than one language—it’s almost always about verbal communication. Yet so very often, the different scripts are what truly hold our abilities to learn new languages back.

The first language I spoke, my mother tongue, was Bengali. My parents recorded me babbling as a baby, fascinated as they were, on cassette tapes in the cramped little flat we lived in. But we lived outside my homeland, so even though Bengali was the one that was nurturing me and giving me the eyes and the vocabulary to perceive the world through, my mother started swiftly teaching me common English phrases on the side. I needed to respond to strangers on the street politely when they greeted me. That wouldn’t work in Bahrain if I only responded in Bengali. So I somehow ended up concurrently speaking English. We moved back to Calcutta and I remember attending nursery school—without uniforms but with fun song and dance time—before joining the primary school. The teachers at the nursery made me speak in English almost exclusively at times (and detected that I was left-handed within the first month of my attending the school, something no family member of mine had even registered in the previous four years). At the end of my nursery education, I spoke English and Bengali at similar competency levels. I had begun to write in both languages as well, the slate and chalk now my constant companions. I don’t remember how my mother managed to teach me two separate scripts at almost the same time. I don’t truly understand how she managed to teach the grammar of the two at the same time—because the grammar is where English and Bengali diverge quite a bit.

Somewhere down the line, I’d managed to pick up Hindi as a language. Perhaps it was the dubbed versions of the Legend of Zorro and Cinderella animations that I religiously watched every evening. It was when we moved back to Bahrain from Calcutta, that my mother told me that she needed me to learn Hindi—and learn it fast. I needed to catch up with my peers who had treated Hindi as their second language in school. That was the first time I had learned a language as a crash course. I am still fairly competent at reading and writing Hindi. I never figured out the logic (or lack thereof) about the gendered nouns and pronouns in the language so I never reached any level of fluency in it. It made me quite biased against languages that have gendered nouns and pronouns, to be honest. I seem to immediately resent them. It’s not a rational response.

I’ve always thought of English and Bengali as my two parent languages, I think in both of them, I dream in both of them, I read and write and speak both in times of happiness and distress. Hindi I have relegated to the status of the third cousin I would rather never speak to again. I put other languages with a plethora of Latinate words in the group of friends I once knew well—thanks to the Latin word tables in my old English grammar textbook—but have now somewhat forgotten. I can probably tell you what the sentence is referring to as a whole, but I have no knowledge of specificity, and I can not understand if a native speaker starts talking to me.

A recent skill that I have picked up is that I can now read Hangul. My Korean vocabulary might comprise only seventy-eight words (give or take a few), but I can read pretty much anything that’s been written down. I haven’t learned a new script since I was seven years old, cramming up to get up to speed with my peers’ Hindi skills. I found Hangul surprisingly simple compared to the Bengali bornomala—we have too many consonants that all sound the same nowadays. I feel obligated to mention that it is so now—one can assume that all the dental, retroflex, and palatal consonants once sounded different, as they’re meant to. Hangul also doesn’t have consonant conjuncts (juktakkhor) the way we do, and it doesn’t have things like যফলা (jophola), which I can’t comprehend trying to explain to someone trying to learn the Bengali script. It is a diacritic, I suppose, but it sounds different depending on where you place it in the word and it is one we use liberally when we’re borrowing words from foreign languages, to mimic sounds that are less frequent in our tongue.

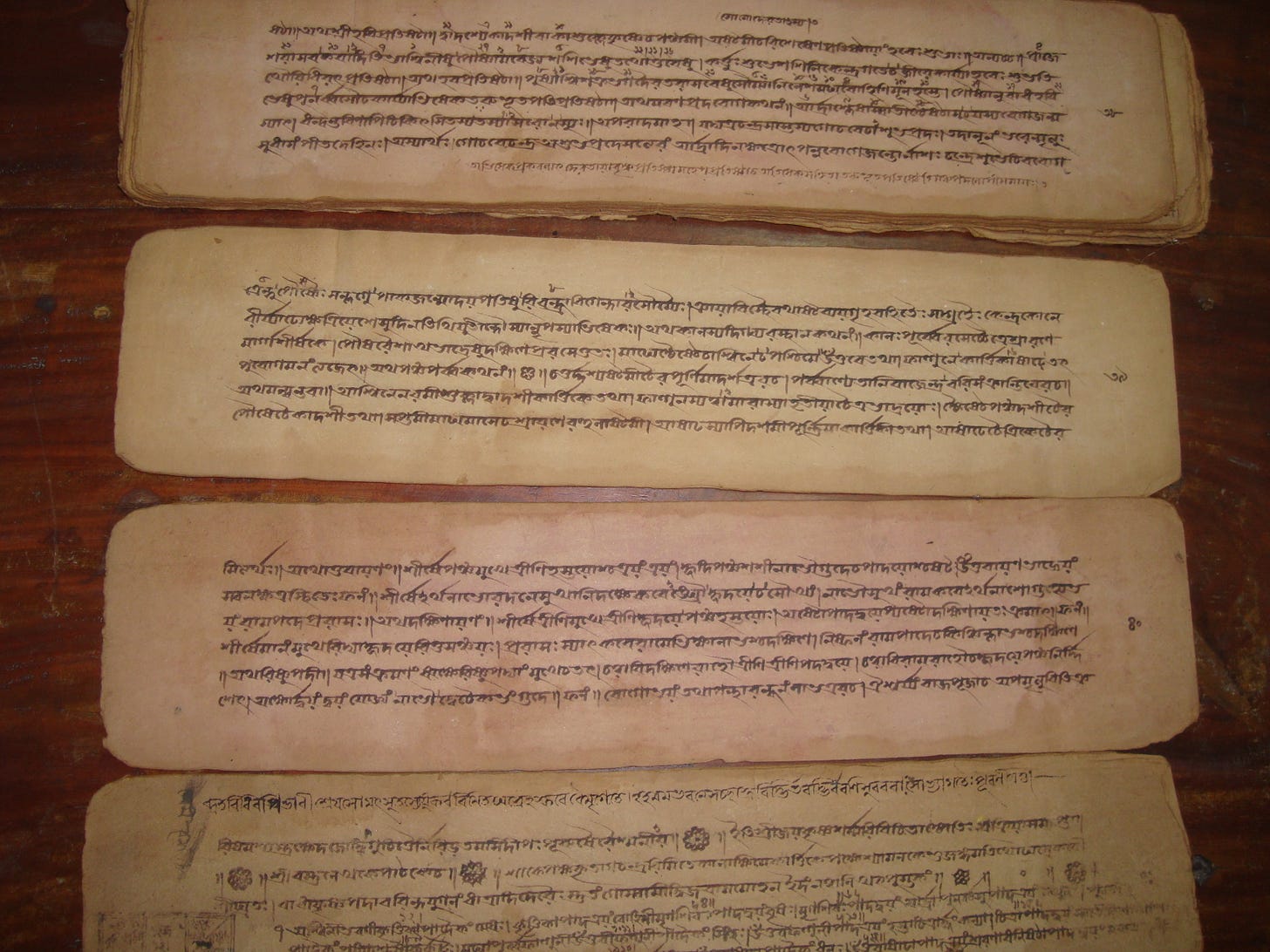

One thing that has fascinated me while picking up Korean has been how much better they’ve held on to correct pronunciation of consonants compared to us. Bengali speakers mispronounce ফ all the time, using an “-f” sound rather than the correct “-ph” sound where you pronounce both the p and the h. I don’t know why we have been losing correct diction culturally. Perhaps this is merely a Calcutta thing. I have spoken to some people from other districts, and if they studied in schools where their first language was English—mine wasn’t, even though the medium of instruction when teaching us all subjects was English—they tend to have even less knowledge about the history of Bengali literature, language, and linguistics. We used to feel slight bouts of despair, having to work our way through Charyapada, but in hindsight, it might have been worth it after all. I don’t feel like I am a stranger in my own mouth.

Part of the rare Charyapad preserved in the library of Rajshahi College. Image credit: Mohmoni, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons